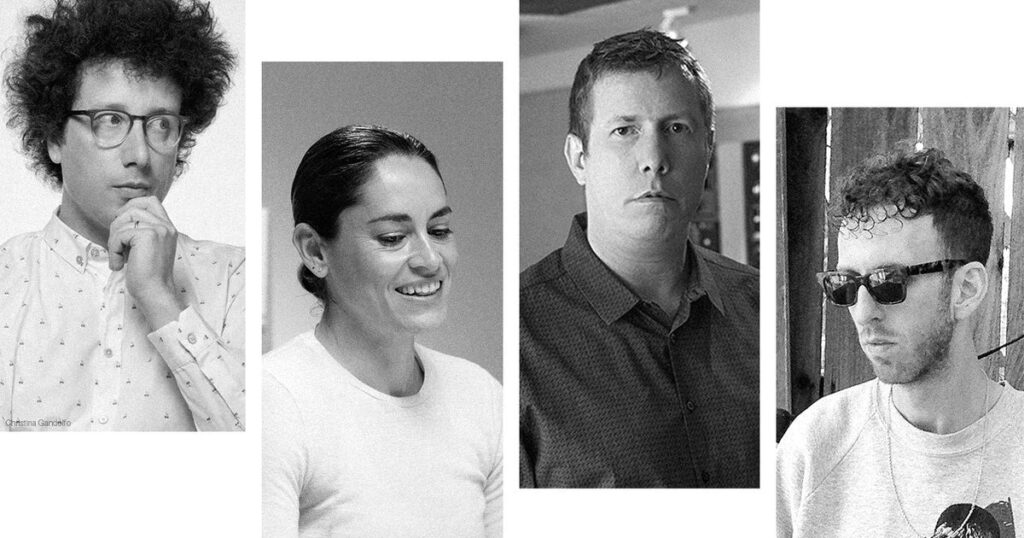

Four producers on the lessons they wished they’d learned sooner.

As music producers, we all remember our early struggles. Muddy mixes, over-compressed vocals, or just that nagging feeling that the sound in your head will never come out of the speakers.

In this roundtable, you’ll hear from producers Justin Meldal-Johnsen, Jennifer Decilveo, Darrell Thorp, and Ariel Rechtshaid as they open up about the hardest lessons they faced when starting out, and the tricks they’ve learned along the way.

When you started producing and mixing music, what gave you the most trouble?

Meldal-Johnsen: I’m a confessed maximalist, so I would endlessly stack reverbs without giving credence to EQ, diffusion, pre-delay, stereo placement, etc. But getting all those elements to live together in a mix was tough.

I also didn’t understand dynamics well enough, which got me into trouble. I remember using a Neve channel strip to annihilate a drum bus, to the extent that it still makes me cringe when I hear it! It wasn’t the good kind of over-compressed, either. It’s very important to fail in order to learn.

Decilveo: I found that my mixes, though dynamic, didn’t occupy all of the areas spatially that I wanted them to. I had difficulty getting that sense of width, or finding the tools to make it happen.

Thorp: I am always striving to ensure that different elements of a mix can be heard. So for me, the hardest concept was clarity. For example, I would listen to parts of a production and think, “that’s bright enough” — though it wasn’t enough to give the entire mix more clarity.

Producing is harder. You’re trying to listen critically to the music, while also being the cheerleader for the session. At the same time, you’re working to keep things moving so it feels like progress is being made. When you’re going for take after take, it’s about making the artist comfortable and giving positive notes about the performance.

Rechtshaid: For me, mixing has become a part of production. I always try to capture an element of the finished vision while I’m producing.

But when I first started, I was scared to take those risks. I just didn’t want to do the wrong thing. For instance, if I was recording drums, I recall being shy about covering the drums with tea towels, or blasting the high end on the snare to get something that reminded me of a Beatles album.

Hozier’s “Francesca,” co-produced by Jennifer Decilveo, blends soaring vocals with brooding, spacious instrumentation.

Is there a certain plug-in or trick you rely on now to solve the issues you’ve faced in the past?

Decilveo: I always have some simple master bus processing to assist with glue and depth. My go-to sounds are the SSL 4000 G Bus Compressor, Pultec EQP-1A Equalizer, and Sonnox Oxford Inflator.

Rechtshaid: For drums, I’ve discovered that adding the SPL Transient Designer on a snare and pulling it way to the left, then adding a little reverb, has become a staple of my sound.

Sometimes, I’ll record bass through the instrument inputs on my Apollo with just a compressor on an insert and realize I like that sound more than a bass amp. Same with guitars — I don’t always need a rare amp like a vintage AC30 or a ’60s Strat. I often plug a modern Strat directly into an Apollo with a fuzz pedal and bypass an amp all together.

Thorp: Early in my career, compression was like a dirty word. I thought people overused it, both on instruments and the mix bus. And I have certainly overdone it with compression a few times in my career.

But now I’ve come to rely on compressors like the UA 1176 Limiter for tone-shaping, as well as volume control. These kinds of tools can be magical for those intentionally over-compressed effects on vocals and bass.

Meldal-Johnsen: This is pretty obvious, but thoughtful high-pass filtering with different settings, slopes, and EQ types. The same goes for saturation or distortion — one size does not fit all. I try to achieve different textures with multiple tools and processes, instead of a single plug-in or effect.

Co-produced and engineered by Justin Meldal-Johnsen, St. Vincent’s “Broken Man” features angular guitar tones, heavy grooves, and a sharp vocal delivery by Anne Erin Clark.

Was there ever a piece of gear or advice that made something “click” for you?

Thorp: Looking back, there was just a day when compression finally made sense. I realized that certain brands or models sounded better on certain instruments, and also how much compression to use for particular types of music.

Rechtshaid: Using UAD plug-ins allowed me to experiment with all these classic sounds at home, without the stress of a high day rate in the studio. I could pull up a Helios Type 69 EQ because I heard Martin Hannett used it on a Joy Division record. Or maybe I heard Tony Visconti used the Eventide H910 Harmonizer on a Bowie song, so I could learn how that worked.

What does 10k on a Neve 1073 Channel Strip sound like? I could crank it on the UAD plug-in, bounce a track, get in my car and be like, “Oh shit, that’s too much!” Or an Ampex ATR-102 Tape Recorder — who knew that if you mess with the bias, you can get different EQ? These plug-ins are all pieces of a puzzle that you get to play with at home. One day, you’ll be in front of the real thing and it will feel familiar.

“UAD plug-ins are like a flight simulator. Once you get in front of the analog gear, you’ll know how to use it.”

Ariel Rechtshaid (HAIM, Vampire Weekend, Sky Ferreira)

Decilveo: I always thought there was a secret to making things sound perfect in the mix. Until one day I was telling David Wrench about my frustrations and asked him how he got his mixes to sound and feel so great. He gave me the best advice: “Use your ears… Keep tweaking until your ears are happy.” That’s been my mantra ever since.

Meldal-Johnsen: It’s so many things! This work is all an aggregate of past experiences and learning.

One realization I’ve had is that the impact of a finished mix typically isn’t helped by elements occupying the same frequency bands. Or likewise, that having more distorted effects doesn’t necessarily make tracks more exciting. I honed in on that concept by the time I was on my second or third album.

In “Capricorn” by Vampire Weekend, Ariel Rechtshaid helped push the band’s sound further with production, drum programming, and lush orchestration.

What advice would you give to someone mixing or producing their first track today?

Decilveo: Every time I work on a project, I just remind myself to use my ears. It’s simple, but it works.

Thorp: That’s it. Listen with your ears, make decisions with your heart or gut. Those are words to live by.

Also, I can sit down all day to listen and mix, but at some point I’m sort of listening blind. The music is coming out of the speakers, but I can’t distinguish the parts anymore. When this happens, it’s usually time to walk away. I’ll take a coffee break, go for a walk, or simply stop for the day. Usually, when I come back fresh the next day, I can quickly find all the missing pieces of the puzzle.

Meldal-Johnsen: Don’t hard-pan everything! But more seriously, I’d urge you to not assume that something can be fixed in post. You have to take the time to get the sound subjectively good the moment you have your hands on it.

Rechtshaid: With all these UAD plug-ins available — Fairchilds, Pultecs, Studer tape machines, room simulators, Fender amps — you have instant access to so many classic sounds. But you may find that what you’re chasing is the performance, and not the gear.

What matters is creating an atmosphere where you can deliver something great. Your focus should go towards the song and the performance.

Darrell Thorp’s role as engineer on Beck’s Morning Phase was central to the record’s sonic identity. Released in 2014, it is praised for its lush, atmospheric production and engineering.

— McCoy Tyler

Related Articles: